On May 2, 2000, Lars Ulrich, drummer for the band Metallica, announced that his group was suing Napster, a free file-sharing service that let fans download music online. During the press conference outside Napster’s headquarters, Ulrich presented the company with a giant stack of papers listing the names of 300,000 Napster users. His assertion: Napster was enabling these people to steal music.

Dramatic optics aside, the issue at hand that day was—and remains—much more complicated than that. It hinges on Americans’ basic misunderstanding of copyright laws. When Ulrich and the music industry argue that file-sharing is theft, they are participating in what I call the “piracy panic narrative,” which goes like this: File-sharing is piracy; piracy is stealing; stealing is negatively affecting recording artists’ ability to make ends meet.

Similar to past panics focused on witches and communists, the piracy panic narrative classifies file-sharers as dangerous enemies. They threaten music, the industry argues, because artists will not write songs if they cannot earn a living from their creative works.

In my new book, iTake-Over: The Recording Industry in the Digital Era, I demonstrate how major record labels produce this panic narrative to secure stronger rights for their industry. Since the public is largely unaware of the mechanics of copyright law, we easily accept the recording industry’s assertion about the illegality of file-sharing—after all, no one wants to steal from their favorite artists. But what we don’t realize is the industry is leveraging this public support to try to change current law so their argument will actually have the legal grounding they’ve claimed it does all along.

In truth, the main barrier to musicians being paid fairly is the recording industry itself, not file-sharers. Record contracts enable the wholesale exploitation of musicians by requiring that artists sign away their own copyrights. As a consequence, they give up their artistic autonomy and a potent source of income. In return for signing a contract, artists receive a monetary advance to record an album, which they must pay back before they see any profits from its sale. They do this with the royalties they earn, but since those usually amount to only 8-15 percent, most artists never make money from their work. Record labels, on the other hand, earn roughly 40 percent of revenue sales.

These record contracts serve as the backdrop for the latest iteration of the piracy panic narrative, which this time targets streaming music services. In a very public move, Neil Portnow, president of The Recording Academy, used the 2015 Grammy Awards to decry the paltry royalties artists receive from streaming services such as Spotify, asking, “What if we’re all watching the Grammys a few years from now and there’s no Best New Artist award because there aren’t enough talented artists or songwriters who are actually able to make a living from their craft?”

His implication, of course, is that if the public does not pay for music, no one will create music. As I’ve explained, this stands in stark contrast to reality, where the vast majority of musicians make no money yet record labels earn millions. Sony Music, for example, has a contract with Spotify that stipulates that the company receive millions of dollars apart from the royalties paid to artists. But Portnow isn’t mentioning this industry-wide exploitation in his appeals to fans.

Ultimately, neither file-sharers nor streaming websites are to blame for the deplorable payments most recording artists receive. The real culprit is the very structure of the contracts every musician must sign—a much more insidious and difficult target to defeat.

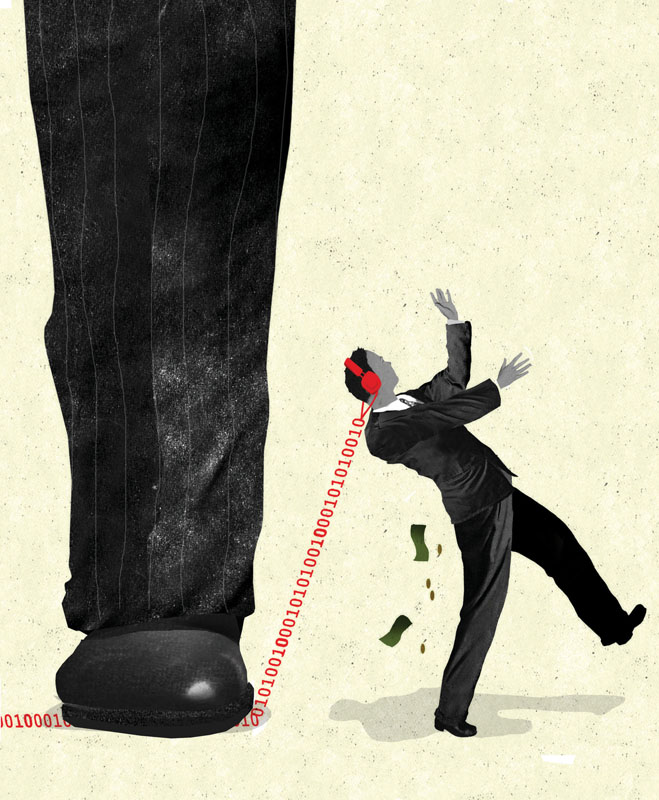

Illustration by Brian Stauffer

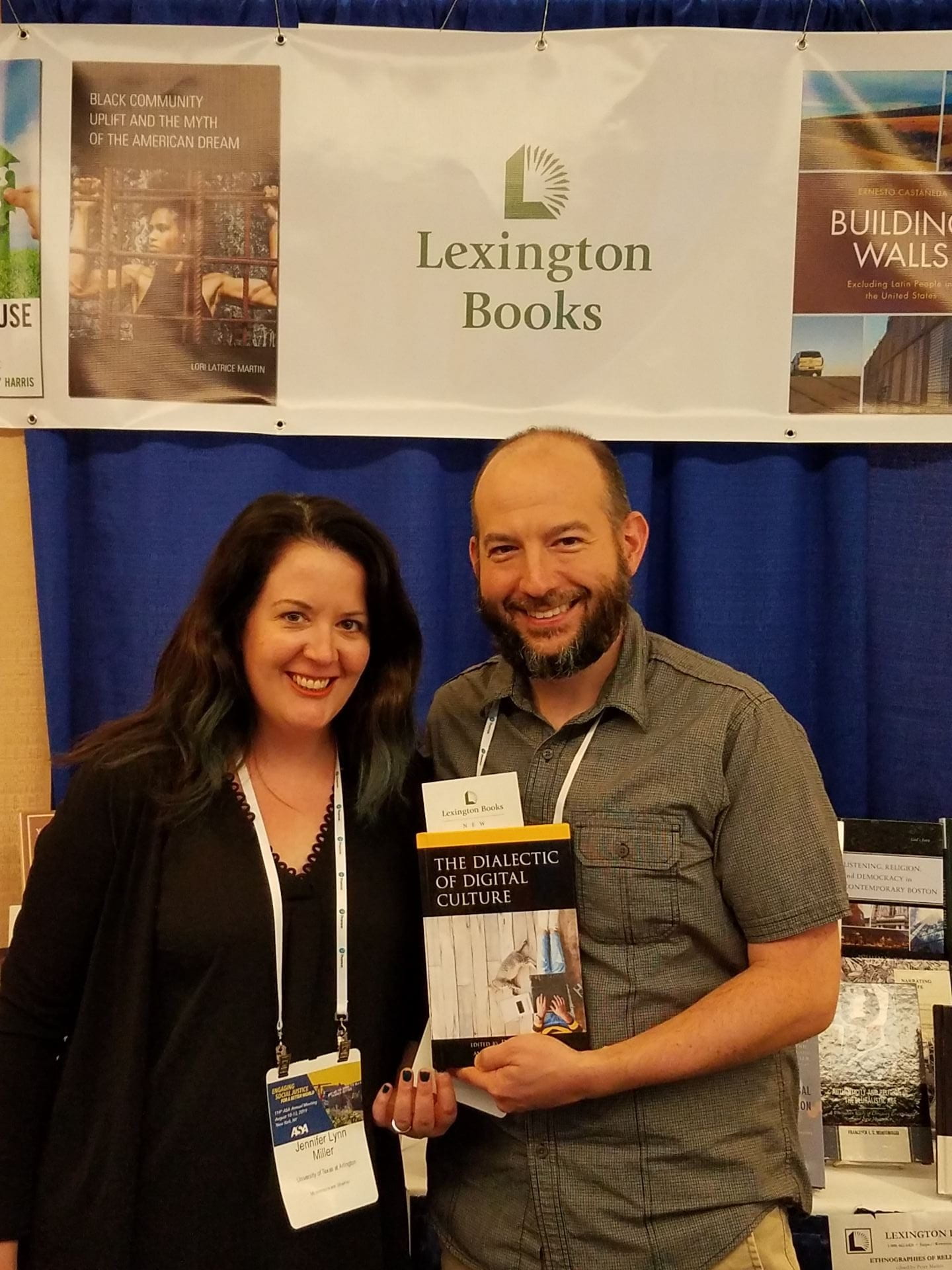

While The Dialectic of Digital Culture was supposed to be published in mid-September, the team at Lexington Press is incredibly efficient and released the book early!

While The Dialectic of Digital Culture was supposed to be published in mid-September, the team at Lexington Press is incredibly efficient and released the book early!