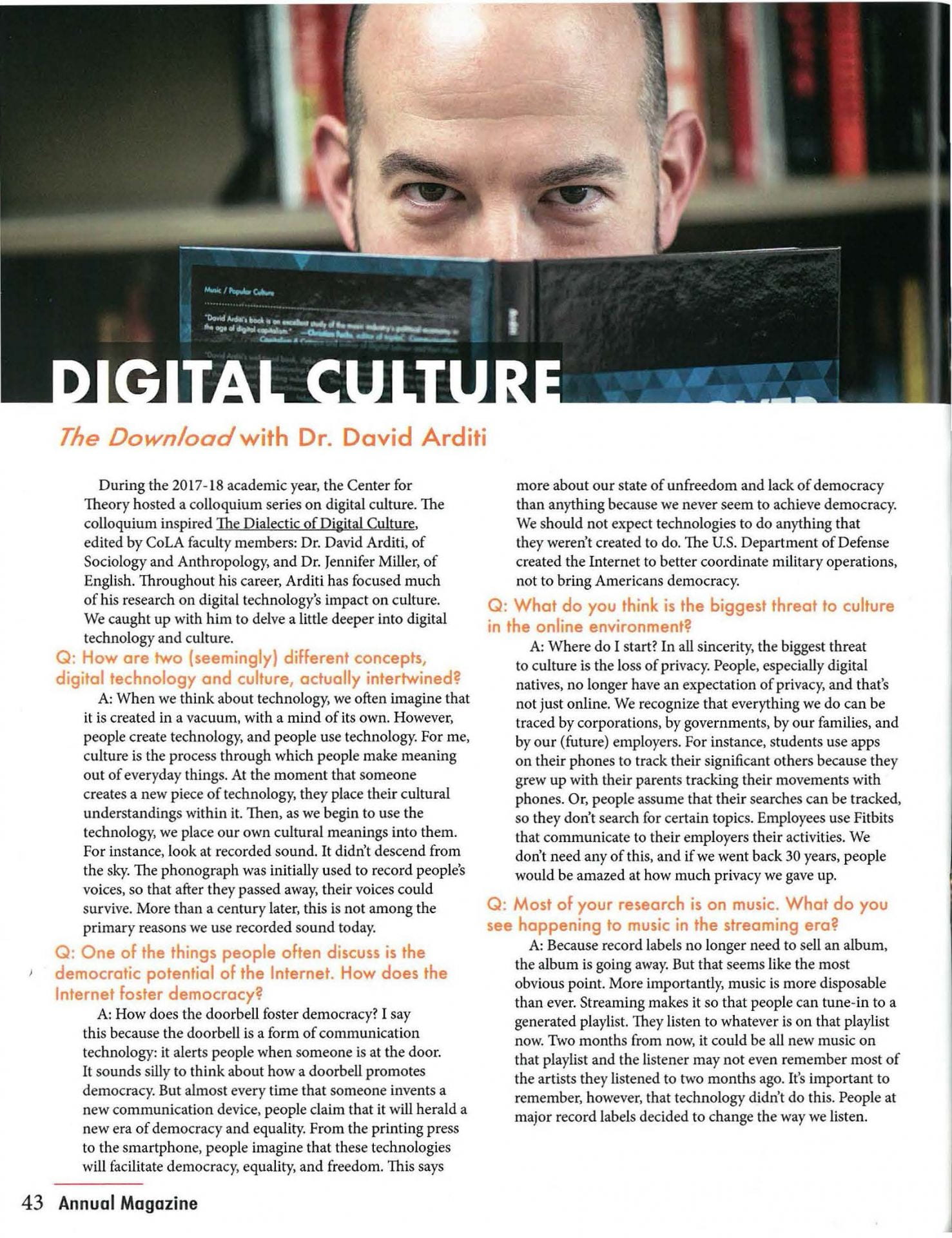

David Arditi, the Director fo the Center for Theory and co-editor of The Dialectic of Digital Culture conducted an interview for The University of Texas at Arlington’s College of Liberal Arts magazine. Read the interview here.

David Arditi, the Director fo the Center for Theory and co-editor of The Dialectic of Digital Culture conducted an interview for The University of Texas at Arlington’s College of Liberal Arts magazine. Read the interview here.

I am the editor of Fast Capitalism. Fast Capitalism is a peer reviewed journal that publishes “essays about the impact of rapid information and communication technologies on self, society and culture in the 21st century.” Our latest issue, 16.2, includes 3 essays that closely align with The Dialectic of Digital Culture. This includes Co-editor Jennifer Miller‘s Essay “Bound to Capitalism: The Pursuit of Profit and Pleasure in Digital Pornography.”

This paper explores digital pornography dialectically through a case study of Kink.com, an online BDSM subscription service. It considers the tension between discourses of authenticity that seek to obscure profit motive and shifts in content prompted by market considerations.

The future of work has come under renewed scrutiny amidst growing concerns about automation threatening widespread joblessness and precarity. While some researchers rush to declare new machine ages and industrial revolutions, others proceed with business as usual, suggesting that specialized job training and prudent reform will sufficiently equip workers for future employment. Among the points of contention are the scope and rate whereby human labor will be replaced by machines. Inflated predictions in this regard not only entice certified technologists and neoclassical economists, but also increasingly sway leftist commentators who echo the experts’ cases for ramping up the proliferation of network technologies and accelerating the rate of automation in anticipation of a postcapitalist society. In this essay, however, I caution that under the current cultural dictate of relentless self-optimization, ubiquitous economic imperatives to liquidate personal assets, and nearly unbridled corporate ownership of key infrastructures in communication, mobility, and, importantly, labor itself, an unchecked project of automation is both ill-conceived and ill fated. Instead, the task at hand is to provide a more detailed account on the nexus of work, automation, and futurizing, to formulate a challenge to the dominance of techno-utopian narratives and intervene in programs that too readily endorse the premises and promises of fully automated futures.

This paper discusses an underrepresented dimension of contemporary alienation: that of machines, and particularly of computing machines. The term ‘machine’ is understood here in the broadest sense, spanning anything from agricultural harvesters to cars and planes. Likewise, ‘computing machine’ is understood broadly, from homeostatic machines, such as thermostats, to algorithmic universal machines, such as smartphones. I suggest that a form of alienation manifests in the functionalist use and description of machines in general; that is, in descriptions of machines as mere tools or testaments to human ingenuity. Such descriptions ignore the real and often capricious existence of machines as everyday material entities. To restore this dimension, I first suggest an analytics of alienating machines – machines contributing to human alienation – and then an analytics of alienated machines – machinic alienation in its own right. From the latter, I derive some possible approaches for reducing machinic alienation. I conclude with some thoughts on its benefits in the context of so-called ‘Artificial Intelligence’.

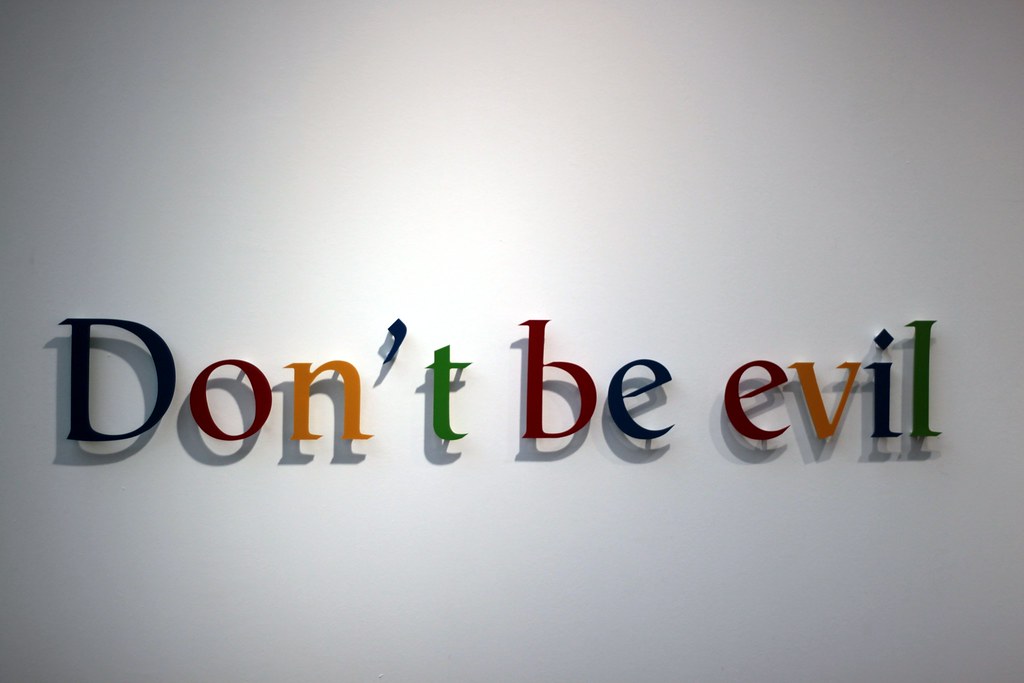

Google’s first motto was “Don’t Be Evil.” This seemed like a fitting title for any tech company that aims to be a force of good (which who doesn’t want to be a force of good). Of course, they removed the motto from the website in 2018. After years of criticism for doing evil things, did this mean they no longer held this to be their motto? Yes, and in 2019 it is quite clear that the opposite is true.

Google’s first motto was “Don’t Be Evil.” This seemed like a fitting title for any tech company that aims to be a force of good (which who doesn’t want to be a force of good). Of course, they removed the motto from the website in 2018. After years of criticism for doing evil things, did this mean they no longer held this to be their motto? Yes, and in 2019 it is quite clear that the opposite is true.

A recent sto ry reports that Google will no longer allow employees to discuss anything but work. Specifically, Google is afraid of being attacked by right-wing ideologues for seeming “liberal” positions. One of those “liberal” positions, I assume is to not be evil. As a result, workers can no can only talk about “facts.” But what is a fact? What types of facts can workers discuss? Who determines which facts are factual? This is especially important in a place highly criticized for its enabling of a post-truth society. How does Google address moderating factual information?

ry reports that Google will no longer allow employees to discuss anything but work. Specifically, Google is afraid of being attacked by right-wing ideologues for seeming “liberal” positions. One of those “liberal” positions, I assume is to not be evil. As a result, workers can no can only talk about “facts.” But what is a fact? What types of facts can workers discuss? Who determines which facts are factual? This is especially important in a place highly criticized for its enabling of a post-truth society. How does Google address moderating factual information?

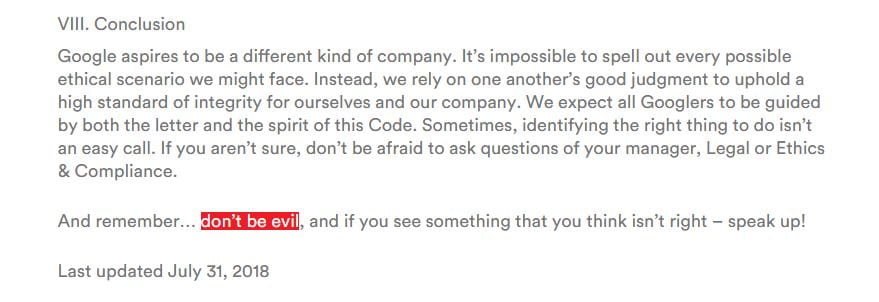

I write this in the context of their motto “don’ be evil.” While it is no longer their motto, it is still part of their code of conduct (though an afterthought).

Determining whether something is evil requires discussion. People need to be able to speak openly and honestly to ensure that they are doing the right thing. In fact, their code of conduct tells employees “don’t be afraid to ask questions of your manager, Legal or Ethics & Compliance.” However, their new rules seem to undo the Code of Conduct.

Determining whether something is evil requires discussion. People need to be able to speak openly and honestly to ensure that they are doing the right thing. In fact, their code of conduct tells employees “don’t be afraid to ask questions of your manager, Legal or Ethics & Compliance.” However, their new rules seem to undo the Code of Conduct.

Employees at Google must be able to discuss more than “facts” in order to make the Internet (which Google is one of the largest monopolies of information on the web) a better place. Now is the time to regulate Google.

A white 30-something male walks through a park at night, and reaches in his pocket to pullout his cellphone. An Asian woman walks down a street at night, and takes her smartphone from her purse. A white woman stops in her kitchen to attend to an app on her smartphone. We get the first glimpse of what catches their attention on their phones, a long-haired white guy wearing a hoodie is at someone’s front door. Another white male wakes up in his bed, wearing pajamas, to view the same video. We see that the Asian woman from earlier sees the same video. We learn for the first time that there is text that goes along with the video:

A white 30-something male walks through a park at night, and reaches in his pocket to pullout his cellphone. An Asian woman walks down a street at night, and takes her smartphone from her purse. A white woman stops in her kitchen to attend to an app on her smartphone. We get the first glimpse of what catches their attention on their phones, a long-haired white guy wearing a hoodie is at someone’s front door. Another white male wakes up in his bed, wearing pajamas, to view the same video. We see that the Asian woman from earlier sees the same video. We learn for the first time that there is text that goes along with the video:

This guy tried to break into my house!

This guy came around the side of my house trying to break in! He ran when I set off my alarm but he may still be in the area

Neighbor 13: I’ve seen this guy before

Neighbor 2: Saw him at my house earlier

Finally, we see a suburban neighborhood with large beautiful homes and pools from the sky. Several dozen homes have a blue halo around them signifying that they use this product. The commercial is for the new app for the Ring doorbell camera. The app, called “Neighbors,” bills itself as the “new neighborhood watch.” The spokesperson says, “At Ring, we want to keep neighborhoods safer, by keeping you informed.”[1]

This advertisement reminds me of my first week in my home in a nice safe neighborhood. My wife and I were walking our 6-month-old son and dog around the neighborhood. An eccentric neighbor began speaking with us, and informed us that her and her husband recently saw a car that did not belong in the neighborhood, and that we need to watch our vehicles because this suspect was probably breaking into ca rs. While we had no further concrete information about the supposed perpetrator, we had an immediate uneasiness about our new neighborhood (over time it has become an uneasiness about that particular neighbor). Maybe the idea behind this app is that I can have further peace of mind that we can come together to chase away potential car thieves or maybe we turn every person whose appearance we do not like into a potential thief. The point of The Dialectic of Digital Culture was to emphasize that the intention of the developers of these technologies is often the latter. In fact, police agencies developed Neighborhood Watch in the 1970s based upon a perceived increase of threats in neighborhoods. However, the perceived threat during the 1970s was always-already racialized, and not based upon actual increases in crime.[2]

rs. While we had no further concrete information about the supposed perpetrator, we had an immediate uneasiness about our new neighborhood (over time it has become an uneasiness about that particular neighbor). Maybe the idea behind this app is that I can have further peace of mind that we can come together to chase away potential car thieves or maybe we turn every person whose appearance we do not like into a potential thief. The point of The Dialectic of Digital Culture was to emphasize that the intention of the developers of these technologies is often the latter. In fact, police agencies developed Neighborhood Watch in the 1970s based upon a perceived increase of threats in neighborhoods. However, the perceived threat during the 1970s was always-already racialized, and not based upon actual increases in crime.[2]

Digital technology infiltrated neighborhoods with community boards long ago. My neighborhood uses the popular “Nextdoor” website. If you feel paranoid, or voyeuristic, you can log on this website and see all kinds of moral panics around perceived folk devils in your community.[3] In one post in my neighborhood, a woman taking a dirty beat-up discarded rug becomes a thief shamed and immortalized on the Internet. We![]() can have disconnected conversations with neighbors we do not know about events we do not understand. But we can all pull together and recognize one thing: we are not safe. Neighbors allows us to use digital technology not only to help alert our neighbors of potential threats, but to raise everything to a potential threat. Already, people are developing lists of best practices with your doorbell camera and police departments started programs to tap into these cameras. Whereas Ring professes they designed the Neighbors App to bring together people in a neighborhood, it will recoil us further into our own little webs as we become scared to show-up on a neighbor’s door unannounced for fear of being painted as an intruder or mocked for what we wear.

can have disconnected conversations with neighbors we do not know about events we do not understand. But we can all pull together and recognize one thing: we are not safe. Neighbors allows us to use digital technology not only to help alert our neighbors of potential threats, but to raise everything to a potential threat. Already, people are developing lists of best practices with your doorbell camera and police departments started programs to tap into these cameras. Whereas Ring professes they designed the Neighbors App to bring together people in a neighborhood, it will recoil us further into our own little webs as we become scared to show-up on a neighbor’s door unannounced for fear of being painted as an intruder or mocked for what we wear.

Furthermore, Ring (and Amazon) partnered with police departments to utilize 911 data to alert people using the “Neighbors” app when their neighbors contacted emergency services. You may be busy changing a diaper, but you can receive an update that your crazy neighbor called 911 because someone let their grass grow too high. Or someone sees a “suspicious” vehicle and alerts the police. Instead of just hearing about your voyeuristic neighbors on the App, you can now hear about every report of any type of incident straight to your phone.

But Ring goes even further with a relationship to the police. Amazon also provides over 225 police departments with access to video footage from Ring (EDIT: The Washington Post is now reporting over 400!). That means that police departments can see what is going on at your front door. Some police even tout it as a service to the community. You think you have a zone of privacy in at your home because you don’t have a Ring doorbell? Only if your neighbors don’t have one either. If someone else’s doorbell faces your home, police can see your home too! Even worse, they can see in your windows if the camera is pointing at them.

While the commercial for Neighbors app demonstrates one creepy level of the digital dialectic, Ring (and its owner Amazon) tries to outdo itself through targeted marketing on social media. The commercial discussed had thinly veiled racial anxieties behind, but Ring goes further. On the morning of February 8, 2019, I witnessed the full extent of the Ring Neighbor App’s pushing racial anxieties when a Ring sponsored post from September 28, 2018 appeared in my Instagram feed. In this ad, four African American men are displayed through the Ring Neighbor App taking packages and breaking into homes in “Culvert City.” The ad ends with “Wonder what’s going on in your neighborhood? Download the free Neighbors App.” Since the App is free, you do not even need the Ring doorbell to participate in your neighborhood’s surveillance. However, a second level of racialized myth emerges from this Instagram advertisement the surveillance targets people from their computer searches. Since I did research on my various devices about Ring and the Neighbors App, Ring targeted me as a potential customer because companies track my every move on the Internet across platforms. This is especially problematic because of the ubiquity of Amazon; the different platforms that I log into with Amazon track me in the background using cookies. For instance, I read The Washington Post (owned by Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO) on my tablet each morning, which I log in using my Amazon account; often, articles about surveillance draw my attention for my research. Amazon uses this information to target me further. While the first ad featured racist conceptions of vulnerable populations, the target of the ad was obscured, but objectified through white privilege. However, in the second ad, Ring recognized me as a white guy and fed into hegemonic white fears of black bodies. These individualized ads target us based on demographic information. Ring and Amazon proudly stoke racist anxieties for profit.

If you’ve ever been around someone with a Ring doorbell (or you own one yourself), you know they create a minor annoyance. Every time a bee flies by the camera, it sends an alert that there is someone at the door. While annoying, it is the least of the problems. Amazon and Ring are developing a surveillance state that knows everything about you and targets your fears and vulnerabilities in order to increase surveillance. We embed these technologies in our everyday lives, but their pervasiveness needs to be analyzed and not accepted.

[1] Neighbors App: The New Neighborhood Watch: https://youtu.be/wRna48aO6gg

[2] Hall et al., Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order.

[3] Cohen, Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers.

While The Dialectic of Digital Culture was supposed to be published in mid-September, the team at Lexington Press is incredibly efficient and released the book early!

While The Dialectic of Digital Culture was supposed to be published in mid-September, the team at Lexington Press is incredibly efficient and released the book early!

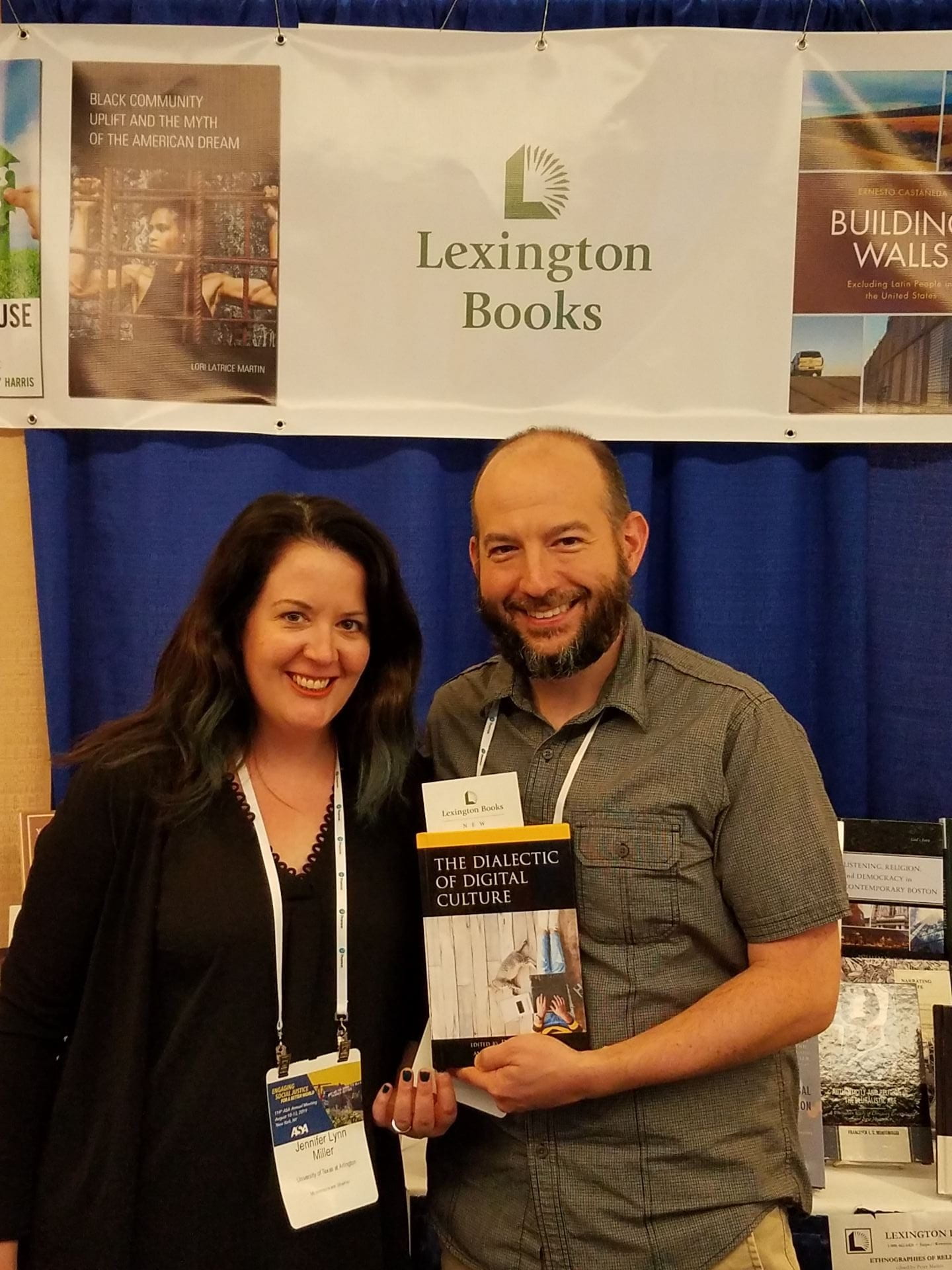

Jennifer Miller and I spent the weekend in New York City attending the American Sociological Association Annual Conference. When we arrived, our fabulous editor Courtney Morales had her copy in print. Then we started receiving emails and texts from contributors that in fact the book arrived. Of course, since we were away from home, we didn’t receive our copies until Wednesday.

The book would not have been possible without the support of the University of Texas at Arlington’s College of Liberal Arts, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Department of English, and the Center for Theory. We’re also grateful for all of our wonderful contributors.

The books look great and I couldn’t be happier with the result. Thank you to Courtney, Shelby Russell, and the rest of the team at Lexington Books. Order your copy now.

Here are some pictures from the American Sociological Association conference.

Several of our contributors will be presenting their research at the American Sociological Association Annual Conference in New York City. Both Editors will be at the conference presenting their research.

On the Critical Theory I: Dialectical Engagements, Jennifer Miller will be presenting her chapter from the  book entitled “Queer Ends: Digital Culture, Queer Youth, and Heterosexuality Beyond Heteronormativity.” Also on that panel, contributors Brian Connor and Long Doan will be presenting “Government vs. Corporate Surveillance: Privacy Concerns in the Digital World.” We hope that you join them to receive a glimpse of the work in the book.

book entitled “Queer Ends: Digital Culture, Queer Youth, and Heterosexuality Beyond Heteronormativity.” Also on that panel, contributors Brian Connor and Long Doan will be presenting “Government vs. Corporate Surveillance: Privacy Concerns in the Digital World.” We hope that you join them to receive a glimpse of the work in the book.

In a similar vein to The Dialectic of Digital Culture, I will be the discussant for Digital and Social Media: Perceptions, Uses and Impact. The papers on this panel present a unique opportunity to think about the digital dialectic in more areas. I’m also presenting my music industry research on the Open Topic on Marxist Sociology. My paper “Copyright as Enclosure: State, Capital, and Primitive Accumulation” explores the way copyright is used to exploit musicians.

Contributor Nancy Weiss Hanrahan will be at the ASA as well serving as a discussant for “Positionality and the Construction of Feminist Theory.”

We want to make it easy for everyone to use The Dialectic of Digital Culture in courses, so we’ll be sharing a syllabus from time to time. Here is an example of how the text can be used in an undergraduate class about Digital Culture. Please email us if you have any questions. dialecticdigitalculture@gmail.com.

Loading...

Loading...

You can now order The Dialectic of Digital Culture. If you order through the Lexington website, you can use the code LEX30AUTH19 to receive a 30% discount.