A white 30-something male walks through a park at night, and reaches in his pocket to pullout his cellphone. An Asian woman walks down a street at night, and takes her smartphone from her purse. A white woman stops in her kitchen to attend to an app on her smartphone. We get the first glimpse of what catches their attention on their phones, a long-haired white guy wearing a hoodie is at someone’s front door. Another white male wakes up in his bed, wearing pajamas, to view the same video. We see that the Asian woman from earlier sees the same video. We learn for the first time that there is text that goes along with the video:

A white 30-something male walks through a park at night, and reaches in his pocket to pullout his cellphone. An Asian woman walks down a street at night, and takes her smartphone from her purse. A white woman stops in her kitchen to attend to an app on her smartphone. We get the first glimpse of what catches their attention on their phones, a long-haired white guy wearing a hoodie is at someone’s front door. Another white male wakes up in his bed, wearing pajamas, to view the same video. We see that the Asian woman from earlier sees the same video. We learn for the first time that there is text that goes along with the video:

This guy tried to break into my house!

This guy came around the side of my house trying to break in! He ran when I set off my alarm but he may still be in the area

Neighbor 13: I’ve seen this guy before

Neighbor 2: Saw him at my house earlier

Finally, we see a suburban neighborhood with large beautiful homes and pools from the sky. Several dozen homes have a blue halo around them signifying that they use this product. The commercial is for the new app for the Ring doorbell camera. The app, called “Neighbors,” bills itself as the “new neighborhood watch.” The spokesperson says, “At Ring, we want to keep neighborhoods safer, by keeping you informed.”[1]

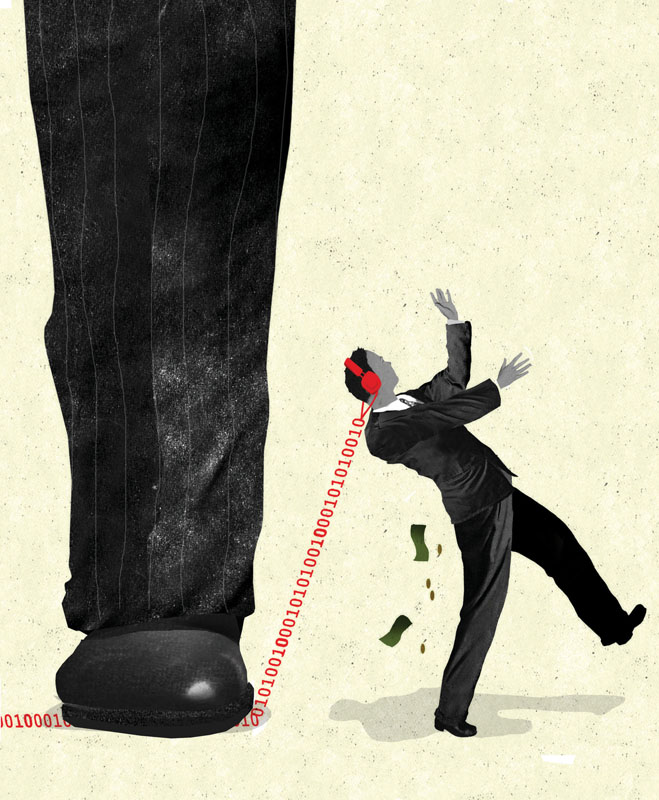

This advertisement reminds me of my first week in my home in a nice safe neighborhood. My wife and I were walking our 6-month-old son and dog around the neighborhood. An eccentric neighbor began speaking with us, and informed us that her and her husband recently saw a car that did not belong in the neighborhood, and that we need to watch our vehicles because this suspect was probably breaking into ca rs. While we had no further concrete information about the supposed perpetrator, we had an immediate uneasiness about our new neighborhood (over time it has become an uneasiness about that particular neighbor). Maybe the idea behind this app is that I can have further peace of mind that we can come together to chase away potential car thieves or maybe we turn every person whose appearance we do not like into a potential thief. The point of The Dialectic of Digital Culture was to emphasize that the intention of the developers of these technologies is often the latter. In fact, police agencies developed Neighborhood Watch in the 1970s based upon a perceived increase of threats in neighborhoods. However, the perceived threat during the 1970s was always-already racialized, and not based upon actual increases in crime.[2]

rs. While we had no further concrete information about the supposed perpetrator, we had an immediate uneasiness about our new neighborhood (over time it has become an uneasiness about that particular neighbor). Maybe the idea behind this app is that I can have further peace of mind that we can come together to chase away potential car thieves or maybe we turn every person whose appearance we do not like into a potential thief. The point of The Dialectic of Digital Culture was to emphasize that the intention of the developers of these technologies is often the latter. In fact, police agencies developed Neighborhood Watch in the 1970s based upon a perceived increase of threats in neighborhoods. However, the perceived threat during the 1970s was always-already racialized, and not based upon actual increases in crime.[2]

Digital technology infiltrated neighborhoods with community boards long ago. My neighborhood uses the popular “Nextdoor” website. If you feel paranoid, or voyeuristic, you can log on this website and see all kinds of moral panics around perceived folk devils in your community.[3] In one post in my neighborhood, a woman taking a dirty beat-up discarded rug becomes a thief shamed and immortalized on the Internet. We can have disconnected conversations with neighbors we do not know about events we do not understand. But we can all pull together and recognize one thing: we are not safe. Neighbors allows us to use digital technology not only to help alert our neighbors of potential threats, but to raise everything to a potential threat. Already, people are developing lists of best practices with your doorbell camera and police departments started programs to tap into these cameras. Whereas Ring professes they designed the Neighbors App to bring together people in a neighborhood, it will recoil us further into our own little webs as we become scared to show-up on a neighbor’s door unannounced for fear of being painted as an intruder or mocked for what we wear.

can have disconnected conversations with neighbors we do not know about events we do not understand. But we can all pull together and recognize one thing: we are not safe. Neighbors allows us to use digital technology not only to help alert our neighbors of potential threats, but to raise everything to a potential threat. Already, people are developing lists of best practices with your doorbell camera and police departments started programs to tap into these cameras. Whereas Ring professes they designed the Neighbors App to bring together people in a neighborhood, it will recoil us further into our own little webs as we become scared to show-up on a neighbor’s door unannounced for fear of being painted as an intruder or mocked for what we wear.

Furthermore, Ring (and Amazon) partnered with police departments to utilize 911 data to alert people using the “Neighbors” app when their neighbors contacted emergency services. You may be busy changing a diaper, but you can receive an update that your crazy neighbor called 911 because someone let their grass grow too high. Or someone sees a “suspicious” vehicle and alerts the police. Instead of just hearing about your voyeuristic neighbors on the App, you can now hear about every report of any type of incident straight to your phone.

But Ring goes even further with a relationship to the police. Amazon also provides over 225 police departments with access to video footage from Ring (EDIT: The Washington Post is now reporting over 400!). That means that police departments can see what is going on at your front door. Some police even tout it as a service to the community. You think you have a zone of privacy in at your home because you don’t have a Ring doorbell? Only if your neighbors don’t have one either. If someone else’s doorbell faces your home, police can see your home too! Even worse, they can see in your windows if the camera is pointing at them.

While the commercial for Neighbors app demonstrates one creepy level of the digital dialectic, Ring (and its owner Amazon) tries to outdo itself through targeted marketing on social media. The commercial discussed had thinly veiled racial anxieties behind, but Ring goes further. On the morning of February 8, 2019, I witnessed the full extent of the Ring Neighbor App’s pushing racial anxieties when a Ring sponsored post from September 28, 2018 appeared in my Instagram feed. In this ad, four African American men are displayed through the Ring Neighbor App taking packages and breaking into homes in “Culvert City.” The ad ends with “Wonder what’s going on in your neighborhood? Download the free Neighbors App.” Since the App is free, you do not even need the Ring doorbell to participate in your neighborhood’s surveillance. However, a second level of racialized myth emerges from this Instagram advertisement the surveillance targets people from their computer searches. Since I did research on my various devices about Ring and the Neighbors App, Ring targeted me as a potential customer because companies track my every move on the Internet across platforms. This is especially problematic because of the ubiquity of Amazon; the different platforms that I log into with Amazon track me in the background using cookies. For instance, I read The Washington Post (owned by Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO) on my tablet each morning, which I log in using my Amazon account; often, articles about surveillance draw my attention for my research. Amazon uses this information to target me further. While the first ad featured racist conceptions of vulnerable populations, the target of the ad was obscured, but objectified through white privilege. However, in the second ad, Ring recognized me as a white guy and fed into hegemonic white fears of black bodies. These individualized ads target us based on demographic information. Ring and Amazon proudly stoke racist anxieties for profit.

If you’ve ever been around someone with a Ring doorbell (or you own one yourself), you know they create a minor annoyance. Every time a bee flies by the camera, it sends an alert that there is someone at the door. While annoying, it is the least of the problems. Amazon and Ring are developing a surveillance state that knows everything about you and targets your fears and vulnerabilities in order to increase surveillance. We embed these technologies in our everyday lives, but their pervasiveness needs to be analyzed and not accepted.

[1] Neighbors App: The New Neighborhood Watch: https://youtu.be/wRna48aO6gg

[2] Hall et al., Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order.

[3] Cohen, Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers.

A white 30-something male

A white 30-something male  rs. While we had no further concrete information about the supposed perpetrator, we had an immediate uneasiness about our new neighborhood (over time it has become an uneasiness about that particular neighbor). Maybe the idea behind this

rs. While we had no further concrete information about the supposed perpetrator, we had an immediate uneasiness about our new neighborhood (over time it has become an uneasiness about that particular neighbor). Maybe the idea behind this

book entitled “

book entitled “