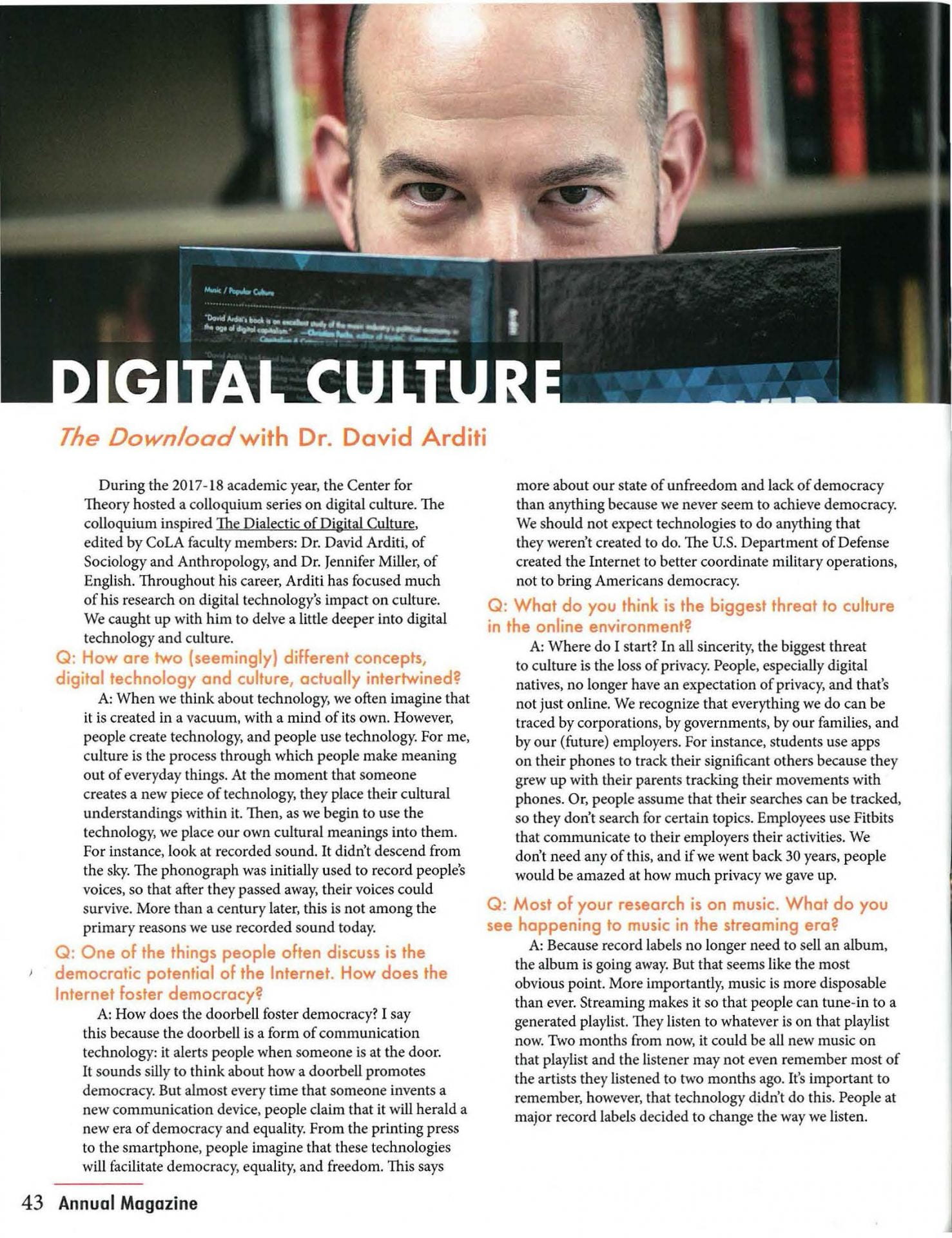

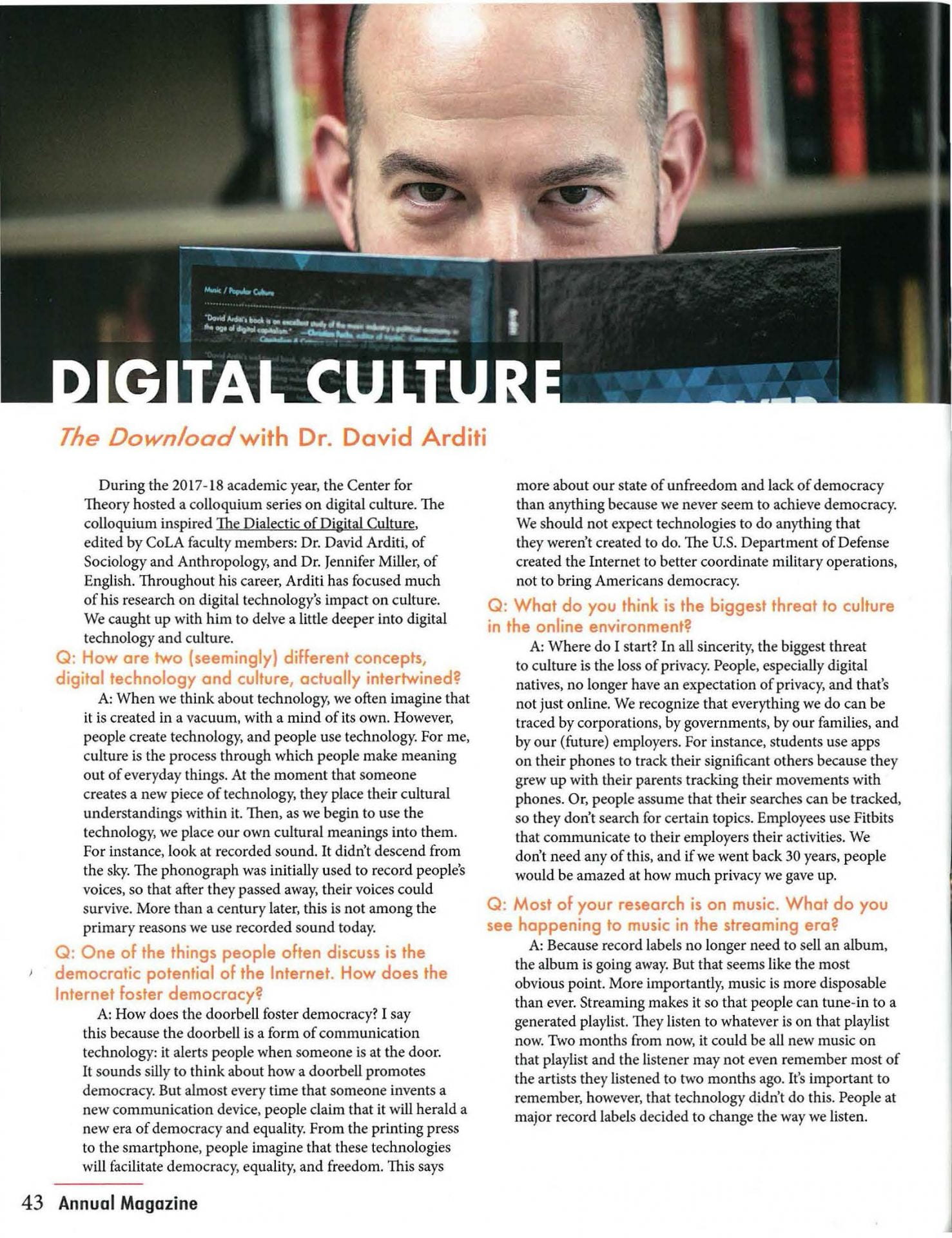

David Arditi, the Director fo the Center for Theory and co-editor of The Dialectic of Digital Culture conducted an interview for The University of Texas at Arlington’s College of Liberal Arts magazine. Read the interview here.

David Arditi, the Director fo the Center for Theory and co-editor of The Dialectic of Digital Culture conducted an interview for The University of Texas at Arlington’s College of Liberal Arts magazine. Read the interview here.

Four of the contributors to The Dialectic of Digital Culture presented at the 2019 National Women’s Studies Association conference in San Francisco, CA. Jennifer Miller, Amy Speier, Ariella Horwitz, and David Arditi presented their work and caught up with Lexington Books’ Courtney Morales, the acquisitions editor. Here are the pictures!

As a professor who studies the intersection between music and digital technology, a few years ago I decided to put knowledge to practice. The result of that work is MusicDetour: The DFW Local Music Archive. MusicDetour has slowly grown over the years, with over 50 artists and close to 300 songs. Recently, I sat down with Katy Blakey of NBC DFW to discuss the website. This is part of NBC5’s “Texas Connects Us” series.

Privacy has been obliterated, Russians  hack our elections, Facebook buys information about women’s periods, Internet Service Providers (ISPs) want to charge more to access certain websites, culture industries want to restrict access to content, the Internet has become a giant mall, free speech has been limited, algorithms feed us the worst of humanity. What does Congress want to do to regulate the Internet? Make the Internet more punitive for people that share cultural content.

hack our elections, Facebook buys information about women’s periods, Internet Service Providers (ISPs) want to charge more to access certain websites, culture industries want to restrict access to content, the Internet has become a giant mall, free speech has been limited, algorithms feed us the worst of humanity. What does Congress want to do to regulate the Internet? Make the Internet more punitive for people that share cultural content.

Today, the US House of Representatives passed The Copyright Alternative in Small-Claims Enforcement (CASE) Act 410-6. Whenever something passes Congress close to unanimously with little debate, it must be about copyright. As I discussed in iTake-Over, Congress allows copyright “stakeholders” to negotiate copyright law and hurriedly pass it. This is the quintessential example of this process discussed by Jessica Litman.

Witness the sponsor of the bill’s language. Rep. Hakeem Jeffries (D-NY) states: “The internet has provided many benefits to society. It is a wonderful thing, but it cannot be allowed to function as if it is the Wild West with absolutely no rules. We have seen that there are bad actors throughout society and the world who take advantage of the internet as a platform in a variety of ways. We cannot allow it.”

Yes! We cannot allow internet companies to operate in a Wild West of unregulated capitalism. I couldn’t agree more! But the solution? Create a small claims tribunal that ignores due process and will allow cultural industries to issue take-down notices. This legislation will do nothing to regulate the Wild West and everything to shutdown free speech further.In all of the public uproar of unregulated tech companies, I’ve never once heard someone say, “we need to make it easier to sue people for uploading unauthorized content.” In fact, most of the arguments have been the opposite — i.e., the Internet provides a place for people to express themselves freely.

Public: We want Congress to regulate tech companies to make the Internet more open.

Congress: We’ll pass a copyright law that makes it less open!!!

The CASE Act will be the hill that Internet regulation dies on.

I am the editor of Fast Capitalism. Fast Capitalism is a peer reviewed journal that publishes “essays about the impact of rapid information and communication technologies on self, society and culture in the 21st century.” Our latest issue, 16.2, includes 3 essays that closely align with The Dialectic of Digital Culture. This includes Co-editor Jennifer Miller‘s Essay “Bound to Capitalism: The Pursuit of Profit and Pleasure in Digital Pornography.”

This paper explores digital pornography dialectically through a case study of Kink.com, an online BDSM subscription service. It considers the tension between discourses of authenticity that seek to obscure profit motive and shifts in content prompted by market considerations.

The future of work has come under renewed scrutiny amidst growing concerns about automation threatening widespread joblessness and precarity. While some researchers rush to declare new machine ages and industrial revolutions, others proceed with business as usual, suggesting that specialized job training and prudent reform will sufficiently equip workers for future employment. Among the points of contention are the scope and rate whereby human labor will be replaced by machines. Inflated predictions in this regard not only entice certified technologists and neoclassical economists, but also increasingly sway leftist commentators who echo the experts’ cases for ramping up the proliferation of network technologies and accelerating the rate of automation in anticipation of a postcapitalist society. In this essay, however, I caution that under the current cultural dictate of relentless self-optimization, ubiquitous economic imperatives to liquidate personal assets, and nearly unbridled corporate ownership of key infrastructures in communication, mobility, and, importantly, labor itself, an unchecked project of automation is both ill-conceived and ill fated. Instead, the task at hand is to provide a more detailed account on the nexus of work, automation, and futurizing, to formulate a challenge to the dominance of techno-utopian narratives and intervene in programs that too readily endorse the premises and promises of fully automated futures.

This paper discusses an underrepresented dimension of contemporary alienation: that of machines, and particularly of computing machines. The term ‘machine’ is understood here in the broadest sense, spanning anything from agricultural harvesters to cars and planes. Likewise, ‘computing machine’ is understood broadly, from homeostatic machines, such as thermostats, to algorithmic universal machines, such as smartphones. I suggest that a form of alienation manifests in the functionalist use and description of machines in general; that is, in descriptions of machines as mere tools or testaments to human ingenuity. Such descriptions ignore the real and often capricious existence of machines as everyday material entities. To restore this dimension, I first suggest an analytics of alienating machines – machines contributing to human alienation – and then an analytics of alienated machines – machinic alienation in its own right. From the latter, I derive some possible approaches for reducing machinic alienation. I conclude with some thoughts on its benefits in the context of so-called ‘Artificial Intelligence’.

As if Amazon needed more promotion, CNET, Washington Post, The Verge, Popular Mechanics, Business Insider, NBC, and many more, covered the event like it is actual news (don’t forget Facebook is doing the same). These tech company events have become part of our culture, but the reporting ignores the deep implications of these technologies. In fact, Amazon outdid itself this time around with its insistence on invading our privacy.

As if Amazon needed more promotion, CNET, Washington Post, The Verge, Popular Mechanics, Business Insider, NBC, and many more, covered the event like it is actual news (don’t forget Facebook is doing the same). These tech company events have become part of our culture, but the reporting ignores the deep implications of these technologies. In fact, Amazon outdid itself this time around with its insistence on invading our privacy.

Most importantly, Amazon created a pair of glasses that have Alexa embedded in them. Because things went brilliantly with Google Glass, Amazon decided, hey, let me get in on that action of resistance to new technologies. With its “Echo Frames”, Amazon will be able to record everything that users see. That includes all of the people out there who do not want to wear Echo Frames, and there’s nothing we can do about it–except declare they’re not allowed in certain places.

Most importantly, Amazon created a pair of glasses that have Alexa embedded in them. Because things went brilliantly with Google Glass, Amazon decided, hey, let me get in on that action of resistance to new technologies. With its “Echo Frames”, Amazon will be able to record everything that users see. That includes all of the people out there who do not want to wear Echo Frames, and there’s nothing we can do about it–except declare they’re not allowed in certain places.

What does Amazon want to do with this? Sell things to you at every turn. Your world with Echo Glasses will be a walking advertisement. You see something and an alert pops up to buy it. Alexa will announce it to you in the new Echo Ear Buds. And talk to you through a ring called Echo Loop. You’ll be tapped into all the ads you could ever dream of . . .

But that’s not all. Don’t forget that Amazon owns the Ring Doorbell. Ring Doorbell and the Neighbors App have deals with police departments across the United States to “share” information from Ring on request. So they will sell this to the police. We also know that Amazon has given Echo data to police in certain circumstances.

We need to be wary of these new technologies. Ask the tough question about why tech companies want to sell them, and think of the implications. As I mentioned in a previous post, newspapers are only concerned (especially the Washington Post) in the most banal ways.

For the first time, an article in The Washington Post becomes  reflective about an Amazon plan. The article “Amazon starts crowdsourcing Alexa responses from the public. What could possibly go wrong?” The newspaper owned by Jeff Bezos, CEO and Founder of Amazon, decides to ask what could go wrong? about the most banal of Amazon plans.

reflective about an Amazon plan. The article “Amazon starts crowdsourcing Alexa responses from the public. What could possibly go wrong?” The newspaper owned by Jeff Bezos, CEO and Founder of Amazon, decides to ask what could go wrong? about the most banal of Amazon plans.

Amazon now allows users to update Alexa’s responses. You can contribute, and through big data, they will pick the most frequent answers. This is really no different than relying on search results. But the Washington Post finally wonders, what could go wrong?

The answer is relatively harmless compared to other things that Amazon does that the newspaper celebrates. Amazon wants to deliver using drones, Alexa listens to everything you do, Ring Doorbell partners with police departments, Amazon automates its distribution centers, Alexa adds cameras–what could go wrong? A lot.

We see Amazon continually encroaching on our privacy – both those who consent and those who do not – exploiting workers, downsizing the workforce, etc. To these issues, the Washington Post is silent. When the national paper of record decides to question the societal impact of an Amazon decision, it is about the most trivial of problematic things that Amazon does.

When I learned about Facebook’s decision to launch a dating service, I was not shocked. After all, Facebook began as a quasi dating service. Zuckerberg started the whole thing with the “relationship status” information. However, by making an explicit dating service, Facebook makes one thing clear: they want all your information. If you use the dating service, not only does Facebook have access to all of your typical data, but they can add your likes/dislikes in other people.

But today, something crazier came out. “UK-based advocacy group Privacy International, sharing its findings exclusively with BuzzFeed News, discovered period-tracking apps including MIA Fem and Maya sent women’s use of contraception, the timings of their monthly periods, symptoms like swelling and cramps, and more, directly to Facebook.” That’s right Facebook bought (they always use the term “share”) information about women’s sex lives and periods.

The amount of information that Facebook retains on its users is obscene. And Facebook’s use is not regulated in any way.

When I started driving, my mom would make me take her cellphone  with me when I left on my own. I lived in the country and drove back roads. My mom was scared that my car would breakdown and I would be stranded for hours. Sure enough my car did breakdown, and I was able to call for help. However, she otherwise forbade me from making phone calls (so few minutes to spare), furthermore, phones were banned from schools. The fear was that something bad could happen and cellphones would save me.

with me when I left on my own. I lived in the country and drove back roads. My mom was scared that my car would breakdown and I would be stranded for hours. Sure enough my car did breakdown, and I was able to call for help. However, she otherwise forbade me from making phone calls (so few minutes to spare), furthermore, phones were banned from schools. The fear was that something bad could happen and cellphones would save me.

Today, not only do new drivers driving in the country have cellphones, now little kids have GPS trackers that announce their every move. Under Armour even makes kid’s shoes with GPS so you can track where they are and make sure they’re not being couch potatoes.

Today, not only do new drivers driving in the country have cellphones, now little kids have GPS trackers that announce their every move. Under Armour even makes kid’s shoes with GPS so you can track where they are and make sure they’re not being couch potatoes.

There is an ugly slippery slope here. First, kids take a cellphone just in case something happens. Second, parents say call me when you get to X. If a parent doesn’t receive the contact, full freak-out mode. Third, the call turned to text. Fourth, some parents realized they could use the phone tracking features on iPhones (originally for lost/stolen phones) to see where there kids were at any given moment. Fifth, apps developed specifically for the purpose of tracking children. Next, these apps became ever-more invasive by sending all texts, calls, emails, web searches, pictures, to their parents. Predictably, kids found ways around this. They turned to Snapchat to send fleeting messages that disappeared form view. They turned off their phones to stop the GPS tracking. They bought burner phones! Finally, parents turned to GPS trackers.

Recently, a study came out that showed this information was freely available online. Part of the problem was the company’s default password. But the password is only part of the problem—the other part is our willingness to give up privacy for a perceived good. This is privacy lost through the voluntary loss of privacy. When we track kids, everyone can track kids, this is not surprising.

My question is, when does tracking kids stop? So you begin tracking your kid for whatever fear as a parent you may have. But when do you stop? You might tell yourself, I’ll stop monitoring texts when she’s 16 and location at 18, but will you? There are certainly legal questions once someone reaches 18, but parents have ways of exercising control over their kids.

Furthermore, the constant tracking changes the tracked. Kids grow up without an expectation of privacy. If their parents can see everything, they change their behaviors and imagine constant surveillance. Then when companies or the state surveil them, they are unsurprised. Why would things be any different? This has massive implications on privacy as a public ideal in the future. In Brian Connor and Long Doan’s chapter “Government vs. Corporate Surveillance: Privacy Concerns in the Digital World,” they wrestle with the distinction between corporate and government surveillance. But this seems to be a new type of surveillance that we should watch: familial surveillance.

In a conversation with students, I learned of something even creepier (to me). People now track their significant others! The apps developed to track kids are now used by people to track their boy/girlfriend/partner/spouse. The students were incredulous: why wouldn’t you want to know where your significant other is? If you can’t track them, you can’t trust them because they MUST be up to no good.

These are systemic issues that we need to explore on the public policy level. It’s not a question of whether or not you opt-in, but rather that opting-out is no longer an option.